Why Farmers Should Grow Trees

Forest planting make sense from a commercial perspective

By Eugene Hendrick1 and Henry Phillips2

The government has recently launched a new forest strategy that aims to increase the level of forest cover from 11% at present to 18% over the period to mid-century and beyond. Many will have heard the programme being promoted on the radio and in other media.

The strategy and accompanying programme aim to deliver a range of ecosystem services which include the provision of wood for fuel, timber and other products. Forests and forest products also play a role in climate change mitigation by removing and storing carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas, and this is a strong driver of the strategy.

A wide menu of grant aid is available under the programme in terms of forest types (FTs), and these are geared to incentivise land owners to plant part of their land. An outline of the programme is available at gov.ie3, while Teagasc has a useful guide to the FTs included and the levels of grants and premium payments available4.

The focus of this article is on the commercial end of the forestry programme - wood production and sale. We show the type of financial returns a land owner can expect by investing part of their land asset into mixed high forests with spruce and broadleaves (Forest Type 12 or FT 12). We also briefly touch on the level of carbon dioxide removals that can be expected from FT 12, bearing in mind that the framework for potentially crediting forest removals remains under development at the EU and national levels.

FT 12 involves establishing spruce forest, typically fast-growing Sitka spruce, with an admixture of a minimum of 20% broadleaves, either mixed through the spruce or in separate blocks. The stocking rate is 2,500 trees per hectare (plants spaced at 2 x 2 metres), which is necessary to produce good quality logs which are easy to fell and delimb, and process into wood products, be that woodchip or wood-based panels from early thinnings, or sawn timber from later felling.

Under the FT 12 category there is an establishment grant of €3,858 per hectare, plus an annual forest premium of €746 per hectare, payable for 20 years for farmers and 15 years for non-farmers. A separate fencing grant is also available.

So what level of income can actually be generated by investing part of a farm or land holding into FT 12.

Income and returns from forest type 12

Income levels depend on premiums, but also, and particularly in the case of spruce crops on growth rates and wood prices.

Following two to three years in the establishment phase when some control of competing vegetation may be necessary, growth will accelerate to 60 to 80 cm a year and the trees will fully occupy the site by age 10 or thereabouts depending on growth rate.

The range in growth rates and commercial wood yield of spruce crops in Ireland is well-established following many years of investigation in trial plots and growth modelling. This work has also shown that spruce growth rates in Ireland are among the fastest in Europe. Essentially this is what makes spruce growing an attractive and profitable investment for the landowner.

Markets for spruce timber in Ireland and the UK are well established and set to expand with the increased emphasis on timber construction to replace concrete and other high carbon emission products. Harvest levels, a reflection of strong markets, have been steadily increasing, and in recent years have reached and exceeded 4 million cubic metres per year.5 The All Ireland roundwood production forecast predicts a harvest level of close to 7 million cubic metres by 2030, with most of the increase coming from the private sector. So, strong markets and a foreseen higher level of use of wood products in construction.

Prices for most categories of wood harvest will vary over time, but owners are in a position to delay or bring forward thinning or final felling harvest according to market prices. A word of caution, final felling too early, at say 25 years, when there may be good prices in the market, can be a false economy. The high rate of growth at that age will mostly cancel out market fluctuations and the level of overall income will be significantly reduced compared to holding the crop for a further five to 10 years. Guidance on the best time to consider final felling is available via the Forst Service felling decision tool6.

Depending on site fertility and exposure the growth of Sitka spruce will vary. Foresters have a number of ways of classifying forest growth rate and productivity. Here we use a commonly used measure of productivity called yield class. It simply tells the forester and land owner how fast the crop is growing and how many cubic metres of commercial wood volume there are likely to be in the forest at a given top height or age. Assortment tables are used to calculate the proportion of different sizes of log in the forest. Using these data sources and timber prices the value of the standing crop at different ages can be calculated.

Using the calculated values and taking into account the forest premium payments on the income side and management and other costs we can calculate the rate of return on the investment of the land asset into forestry (assuming the land is owned by the farmer). We also calculate what is called the net present value (NPV), also called present value. It brings all the costs and income to the present day at a certain rate of interest. It’s a way of saying how would you value a series of future costs and revenues if they were all to happen in the current year.

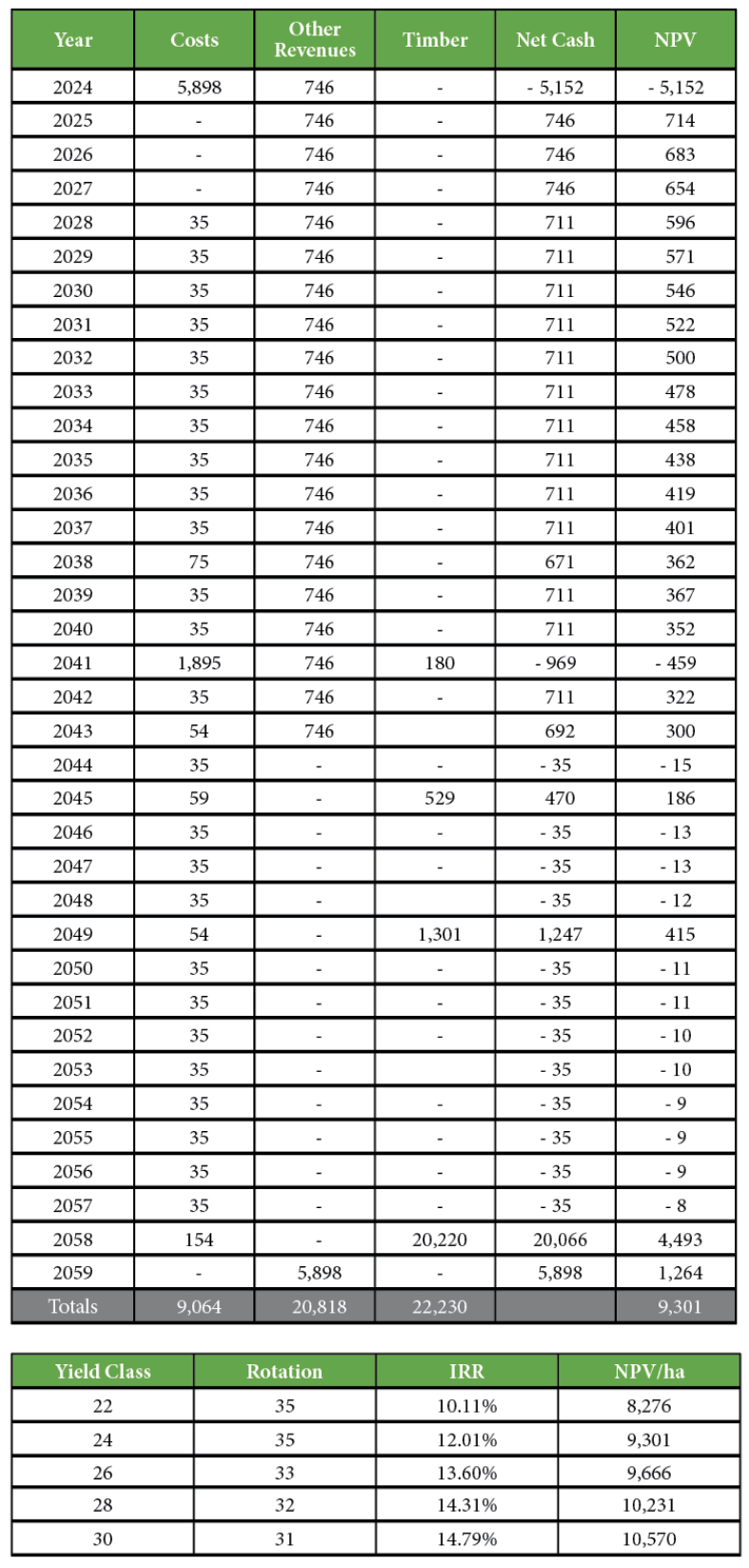

For example, the table below assumes that prior to afforestation the land is used for rearing cattle. Based on the recent Teagasc farm survey this yielded an average €316 per hectare in annual income in 2021. The NPV of this annual income forgone was calculated at 4%. At the end of the rotation the value of the land is credited back to the farmer. Income from BISS (Basic Income Support Scheme) payments is not included in the analysis, nor payments to flat rate farmers i.e. those not registered for VAT based on the timber revenues. If landowners qualify, they can charge 5.6% on timber revenues and keep this income for themselves in lieu of VAT payments on other goods and services. The normal costs for maintenance, roading, licensing etc are included. The planting assumes 72% spruce, 18% broadleaves and 10% biodiversity/open space. The revenues are based on a three thin model and seven-year average prices. The discount rate used was 4.5% which approximates the current market discount rate. Finally it is assumed that the grant payment fully covers the cost of establishment up to year four.

The table shows the progress in growth and income, as well as costs per hectare for Sitka spruce plantation at yield class 24. NPV is the net present value. The crop is grown for 35 years and is thinned three times. The main income is from timber sales, and at final felling the estimated income is over €20,000 per hectare.

Using the same approach as in the above table we have calculated the net discounted revenue and internal rates of return for a range of yield classes, and these are summarised in the table below.

The internal rates of return from the analysis range from over 10% to close to 15%. The higher yield classes are more the exception than the rule, so the IRRs are likely to be in the range 10-13%. These represent the rate of interest that a FT 12 forest assert can attain over three and half decades. These rates compare well with the rates obtainable from most other asset classes, and from most types of farming. Noting of course that the calculations exclude the cost of land, and refer to returns where a land owner invests part of their asset into commercial forest. Nevertheless, for a land owner the attractions of investing in forest are clear, and forest income is not subject to income tax.

Where the forest is to be worked using thinning a minimum area of around 5 hectares is required to pay for machine movement costs. Smaller forest areas can be economically managed if thinning is not considered, though cash flow analysis shows that thinned forest will yield a higher level of return to the owner than unthinned forest.

Climate change mitigation

One of the main aims of the government’s policy to expand forest cover in order to address national and EU climate goals to radically reduce greenhouse gas emission – at the national level the target is to reduce emissions by half by 2030 compared to 2018 levels.

Our colleague Dr Kevin Black7 has estimated that FT 12 with a yield class 24 crop has an average removal rate of 9 tonnes of carbon dioxide per hectare per year, up to a maximum of 300 tonnes of carbon dioxide per hectare. In other words, if the carbon uptake in the forest is to be balanced with emissions from say dairy cattle, 300 tonnes per hectare is the maximum amount that could be offset. As we note, the exact mechanism for crediting forest removals under the EU’s carbon farming initiative have yet to finalised, although there are several so-called voluntary carbon market initiatives related to afforestation and forest management in existence.

Conclusions

Forest Type 12 will provide good rates of income and returns on land converted to a forest asset. For example by devoting an area of 5 ha to forest will generate a tax-free income in the range of €100,000 after 35 years, as well as intermediate income from forest premium and timber sales from thinnings.

The same 5 has the potential to remove some 1,500 tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and contribute to climate change mitigation at farm and national level.

Further information on FT 12 and other forest types is available from Teagasc or from the companies and individuals listed at forestry.ie

- SmartEarth – smartearth.ie – forest policy and climate change analyst – eugene.hendrick@smartearth.ie

- Forestry consultant – forest valuation and forecasting - hprphillips@gmail.com

- https://assets.gov.ie/268252/59e8729c-9e6a-4221-bbc6-d1a5d9fa2f44.pdf

- https://www.teagasc.ie/crops/forestry/grants/

- cubic metre of freshly-felled spruce at say 55% moisture content weighs about 0.8 tonnes. Timber stacked in an open space over the summer drying period can dry to a moisture content of 40% and lower, and now 1 cubic metre will weigh about 0.6 tonnes because of moisture loss. As a result, it is better to transact wood sales in cubic metres than in tonnes.

- gov.ie - Tree Felling Licences (www.gov.ie) or https://forestry.designwest.ie/public/

- Dr Kevin Black is Forest Ecologist and GIS Analyst at Forest, Environmental Research & Services (FERS) Limited – fers.ie. He compiles national greenhouse gas inventories for the forest sector on behalf of the Department of Agriculture Food and Marine and the Environmental Protection Agency, as well as advising a number of other government departments and agencies on the land use, and-se change and forestry (LULUCF) sector.